New Fellow Bootcamp Series: HIT/HITT

An exciting new academic year is about to begin. We know this can be daunting, especially for our newest hematology/oncology fellows. Over the next two weeks, we re-boot some of our high yield episodes you need to know to prepare for your first days as a new fellow and your nights on call.

Next up: Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia! [Originally episode 071]

Be sure to check out our Rotation Guides to get you in tip-top shape for fellowship!

What are the important things to understand about platelets?

Platelets breaking off from megakaryoctyes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GTZCCyHljCk

Platelets are actually cell fragments that break off from megakaryocytes. Platelets contain granules that, when released, facilitate the formation of a clot

Alpha-granules include >200 proteins involved in the clotting process. Platelet factor 4 (PF4) is one of the proteins found in alpha-granules

Proper function of platelets requires a complex mechanism to ensure degranulation occurs at the right time in order to initiate and sustain the clotting cascade. As such, inappropriate platelet activation can cause pathologic clotting.

What are HIT and HITT?

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) was first described in 1958 when some patients would receive a blood thinner and paradoxically develop thrombosis as well as thrombocytopenia

There are two types of HIT: type I and type II

Type I HIT is a transient, non-immune reduction in the platelet count that can occur within minutes due to platelet agglutination

Type II HIT is an immune phenomenon where patients develop an antibody when exposed to heparin that results in a significant drop in the platelet count as well as a very high risk for thrombosis. This is the clinically relevant and pathologic process that we will be discussing in the remainder of this episode

HIT is intensely pro-thrombotic and we use the term HITT to refer to cases of HIT with thrombosis

At the time of diagnosis, 50% of patients will already have a thrombosis.

If not anticoagulated, half of the remaining patients will develop either a venous arterial thrombosis within the next 30 days.

Overall, there is a 12-15x risk of thrombosis (arterial or venous) compared to patients without HIT

Why does HIT happen?

Image source: Figure 2: Gowthami M. Arepally; Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood 2017; 129 (21): 2864–2872.

PF4 is a tetramer that is positively charged. Heparin is a long chain of negatively charged molecules.

In states of PF4 excess or heparin excess, there is a charge imbalance that causes electrical repulsion and limits the formation of large complexes

However, when both PF4 and heparin are present in a certain stoichiometric ratio the attraction from opposing electrical charges lead to the formation of a large complex. This complex is stable due to having an overall neutral electrical charge

These large complexes are what are known as “haptens”, meaning that compared to the individual components they are relatively immunogenic.

When recognized by a constitutively active IgM against PF4/heparin, this can trigger class switching to IgG and the production of large amounts of anti-PF4/heparin IgG (aka, the HIT antibody) due to clonal expansion.

The HIT antibody can bind to the Fc-gamma receptor on platelets causing them to be activated. This results in degranulation, which is the first step in the clotting cascade and promotes thrombosis through a variety of substances contained in the alpha-granules.

This is the reason why HIT (also known as HITT when thrombosis is occurring) is considered an intensely pro-thrombotic state (12-15x increased risk of thrombosis).

What are the risk factors for HIT antibody formation?

It is important to understand that the presence of a HIT antibody does NOT necessarily mean that the pathologic process of HIT is occurring.

HIT antibodies can be found in 0.3-0.5% of the population. This is theorized to be linked with infections or inflammation from surgery.

Very rarely, this can actually lead to spontaneous HIT without antecedent heparin exposure.

The two main risk factors for developing HIT antibodies are the clinical setting that a patient is in and the type of heparin-based anticoagulant that they are exposed to

The incidence of developing HIT antibodies in patients undergoing cardiac surgery and receiving intraoperative unfractionated heparin (UFH) is as high as 50%

Patients on Med-Surg floors receiving UFH have an incidence of HIT antibody formation of 8-17%

Patients on Med-Surg floors receiving low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or fondaparinux have an incidence of HIT antibody formation of 2-8%

The true incidence of HIT (ie, the pathologic process and not simply antibody formation) is estimated to be 0.5-1%

Note that while the incidence of both HIT antibody formation and pathologic HIT is higher with UFH vs LMWH when given at prophylactic doses (7.8 vs 2.2% for antibody formation and 2.7% vs 0% in one study), when used at therapeutic doses the incidence of pathologic HIT appears to be relatively similar.

Diagnosing HIT

Step 1. What is the 4T score and what is it useful for?

The American Society of Hematology produced guidelines to evaluate the pretest probability of HIT rather than using a physician's gestalt. A systematic review and meta analysis by Cuker et al in Blood 2012 concluded that patients with intermediate and high probability scores required further evaluation.

One caveat to note, there is ongoing research about the validity of the 4T score in critically ill patients. It is important to think critically in these cases.

The 4T score has its limitations, and should be thought of as a way to estimate the likelihood of a positive ELISA rather than the direct likelihood of truly having HIT. If the 4T score is low, further testing can likely be deferred since HIT is very unlikely. If the 4T score is high or intermediate, it indicates further testing is necessary for evaluation.

Step 2. When should you send an ELISA test and what does it tell you?

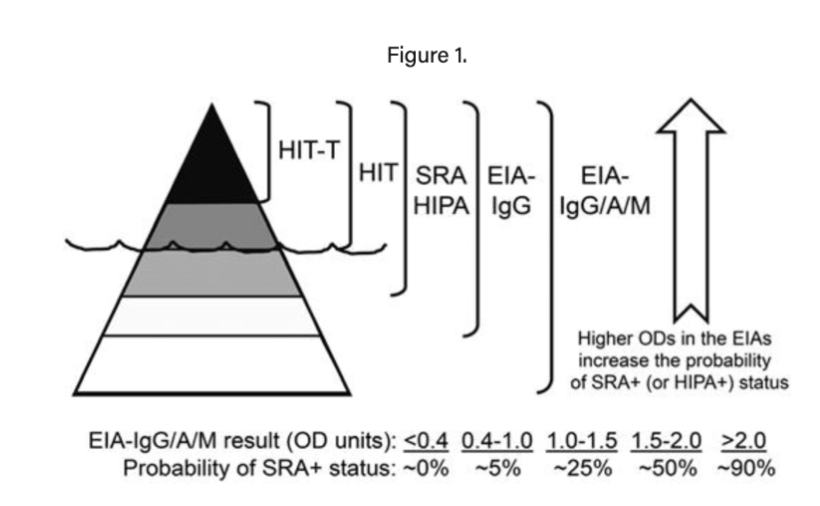

If the patient has high or intermediate risk, send an immunoassay (ELISA). Note that this test is useful for detecting whether a HIT antibody is present, however in and of itself it is not diagnostic for the pathologic process of HIT.

The best way to think of ELISA testing is that it allows you to estimate the probability of a positive serotonin release assay (SRA), which is the actual diagnostic test. Low OD on an ELISA can be used to safely rule out HIT and defer SRA testing, which is a more expensive and time-consuming test that typically must be done as a sendout.

Important note: if you reach this point, ensure you stop all heparin products and switch to an alternative anticoagulant given the high risk for thrombosis if HIT is truly present.

How does the immunoassay work? It is an ELISA test:

A commercially available plate with heparin-PF4 complexes is purchased.

To this the patient’s serum is added, which presumably has the HIT antibodies in it. HIT antibodies will bind to the heparin-PF4 complex.

Then an Anti-IgG antibody with a chemical linker is added that will bind to the HIT antibody (if present). A substrate is added which changes the color of the chemical linker and the color change is then recorded. The units are as optical density.

Image source: Ronak Mistry

Adapted from: https://derangedphysiology.com/main/required-reading/haematology-and-oncology/Chapter%201.2.1.1/heparin-induced-thrombocytopenia

Image source: Figure 1. Warkentin TE, Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program; 2011.

Step 3. How do you use a serotonin release assay to diagnose HIT?

If the immunoassay (above) is positive, obtain a functional assay (serotonin release assay) to actually make the diagnosis.

Serotonin Release Assay:

The amount of serotonin release is proportional to the severity of HIT

Technically challenging test.

Lab techniques and the set up: every an SRA is run, a person from a donor pool whose platelets we know work in this assay needs to be called in to donate platelets

This test is not readily available, usually requires send out to reference labs, meaning it will take many days to result.

How to run a Serotonin Release Assay:

Take the patient’s serum with presumed HIT antibody

Call in a donor from the community who’s platelets are known to respond in a predictable way

Incubate platelets from the donor with radiolabeled serotonin (labeled with carbon 14)

Combine C14 radiolabeled donor platelets, patient’s serum, and a variety of concentrations of heparin

Looking for antibody that causes platelets to degranulate and release the radiolabeled serotonin at a therapeutic concentration of heparin but to be suppressed with a supratherapeutic concentration of heparin

This is because the rafts of PF4 and heparin cannot form if supratherapeutic.

Why? You are disrupting the necessary stoichiometric ratio needed to carry out the process when the super high doses of heparin are added

A positive SRA is defined as >20% serotonin release, though usually it’s more like 80% release.

If a patient has a positive SRA, then they have HIT

Image source: Ronak Mistry

Adapted from: Warkentin TE, Arnold DM, Nazi I, Kelton JG (2015) The platelet serotonin-release assay. American Journal of Hematology 90:564–572. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24006

Step 4. If ELISA and SRA are positive, ensure patient continues on non-heparin anticoagulation

What are the options for alternative anticoagulation, and when can you transition from one agent to another?

Typically, we use alternative IV anticoagulants for initial management until platelets are 150,000/mm3 as patients can simultaneously be at high risk for both bleeding (from thrombocytopenia) and clotting - this allows us to rapidly turn anticoagulation on and off.

Once >150,000/mm3, transition to an oral agent, such as a DOAC or fondaparinux. Fondaparinux is able to be used in this situation because it is subtherapeutic and does not run the risk of creating the PF4-heparin complexes.

How long should patients be anticoagulated for?

HIT: continue anticoagulation for 1 month after platelet recovery

HIT-T (HIT with thrombosis, ie why the 4 extremity doppler is essential): continue for 3 months after platelet recovery, as if you were treating a new clot.

Other practical points:

Other than alternative anticoagulation, what else should we consider going in these patients?

4 extremity dopplers should be performed due to a higher rate of thrombosis with HIT. This will change the anticoagulation plan if positive.

If a patient is on warfarin, reverse it with Vitamin K ASAP.

This is because remember warfarin works by impairing the ability to make vit-K dependent factors in the clotting cascade, which includes Protein C and which are ANTICOAGULANTS. Protein C has a shorter half-life so you don’t want that to go down before the rest of your factors.

Add heparin to the allergy list.

Note that it is generally accepted that there is no long-term anamnestic response (ie, the body will not have memory B-cells making antibodies against HIT antibody long term), however despite this we typically avoid re-challenging with heparin products unless necessary

One reason that you may want to challenge many years down the line, is the need for extensive cardiac surgery requiring extended time on cross clamp or bypass machines. The alternative, bivalirudin has not performed well in these conditions, as it gets inactivated in stagnant blood.

The crew behind the magic:

Show outline: Ronak Mistry

Production and hosts: Ronak Mistry, Vivek Patel, Dan Hausrath

Editing: Resonate Recordings

Shownotes: Sean Taasan, Megan Connor

Social media management: Ronak Mistry