Episode 050: #NephMadness Onconephrology - ICI-Associated AKI and Chemotherapy-Related Hypomagnesemia

The Fellow on Call is thrilled to partner with so many of our podcasting friends be a part of #NephMadness 2023 this year. In today’s episode, we welcome three incredible guests to our show, Dr. Matthew Abramson, Dr. Timothy Yau, and Dr. Scott Stockholm, to talk about the two very critical topics in hematology/oncology. The first is a discussion about immune checkpoint inhibitor-related AKIs. The second is a discussion about hypomagnesia in our patients. To learn more about NephMadness and to cast your votes, be sure to check out: https://ajkdblog.org/tag/nephmadness2023/. We’d love to see Onconephrology snag that #1 spot :)

Love what you hear in this episode? Be sure to check out all the #NephMadness fun with our friends!

Match up #1: Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated acute kidney injury

How do checkpoint inhibitors work?

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have caused a dramatic shift in cancer therapy over the past decade since their introduction with FDA approval of ipilimumab in 2011.

They are now first and second-line therapies for more than 50 types of cancer. The ability to achieve long-standing or complete remission in previously nearly incurable cancers (e.g. melanoma) has been revolutionized by these drugs.

Mechanism of action: Normally, T-cells have immunologic brakes that prohibit them from attacking “self” tissue of the host organism. ICI’s remove these brakes to permit T-cells to target and destroy cancer cells.

There are three major categories of ICI’s: CTLA-4 inhibitors, PD1 inhibitors, and PD-L1 inhibitors

However, in the process of blocking these immunological checkpoints, autoimmune phenomena can occur (termed immune-related adverse events, or irAE’s). This commonly takes the form of dermatitis, pneumonitis, colitis, or thyroiditis, but I have seen a few patients get kidney irAEs as well.

What kinds of AKIs are you seeing with immune checkpoint inhibitors?

The largest retrospective case series have shown 3-5% from immune checkpoint inhibitors

Need to always rule out other causes of AKIs

Most commonly an acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (essentially an allergic reaction in their tubules)

No blood or protein should be seen on the UA

What is the workup for a suspected immune checkpoint inhibitor?

The most important thing is taking a good history and physical:

Is the patient volume depleted? Is there history of nausea/vomiting/diarrhea? How do they look on exam?

Many patients will also have other adverse reactions, as well: rashes, colitis, hypophysitis, etc.

Sending typical labs for AKI workup:

Is creatinine acutely worse or has this been happening over a period of time?

Consider renal ultrasound to rule out post-renal etiology

Obtain a UA

If pre/post-renal ruled out, and likely intra-renal etiology, the UA will is very helpful:

If you see blood and protein → suggests nephritic or nephrotic disease, which suggests glomerular disease. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced AKI does NOT affect the glomeruli

If you see WBC/WBC casts without evidence of infection → more consistent with immune checkpoint mediated damage

When you see blood and protein in the urine (more than trace), that signifies that there is glomerular disease

If there’s no blood or protein and only WBC/WBC casts that is more likely tubulointerstitial nephritis, which is how immune checkpoint inhibitor-mediated AKI can present

If UA is entirely bland, it can still be tubulointerstitial nephritis; in retrospective studies, 50% of cases will have bland UA

BUT the absence of blood suggests that it is likely not glomerular disease

Is there any association between PPI use and immune checkpoint inhibitor related AKI?

An association, but unknown exactly how that works. May be like a “second hit.”

Stop PPI if you do suspect immune checkpoint inhibitor related AKI

Are there any renal manifestations other than tubulointerstitial nephritis as renal manifestations of ICI related AKI?

90% are tubulointerstitial nephritis

Other etiologies are rare (case-reports at best):

ANCA-associated Vasculitis

IgA nephropathy

FSGS

Minimal change disease

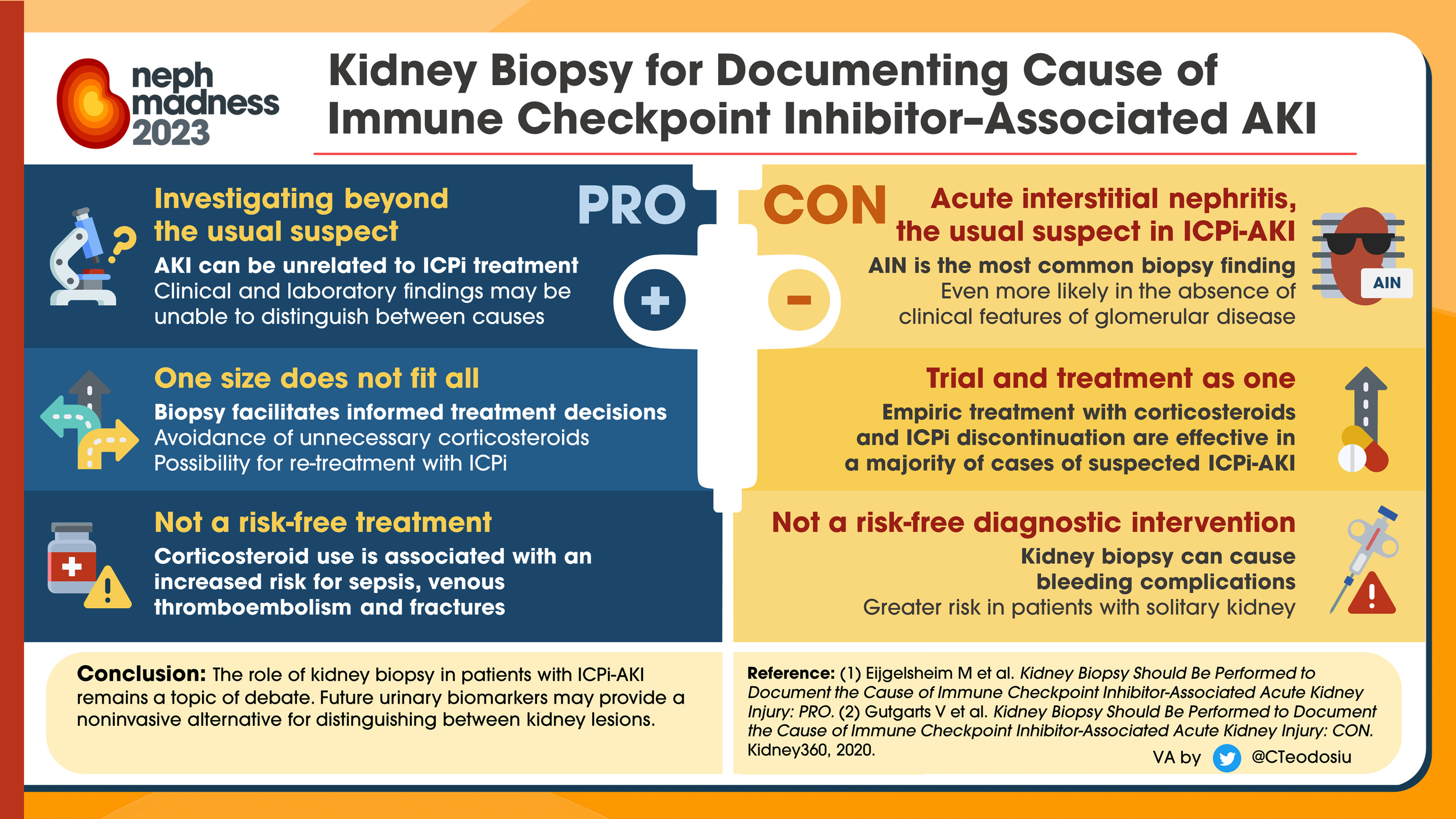

At what point should we think about empiric steroids or to pursue a biopsy?

A patient with a mild/moderate AKI without glomerular disease, reasonable to treat with steroids

If steroid response is suboptimal or severe AKI or glomerular signs on workup, then consider biopsy because the treatment will be worker

When deciding on a biopsy, remember that patients will need stable platelets, hemoglobin, etc. So we need to have a multidisciplinary discussion about pros vs. cons

The biopsy can be helpful depending on the clinical picture so that we know what we are dealing with if it safe to do

This is especially important if patients have had great response to their immune checkpoint inhibitor, as this can affect future treatment options for the patient

(Source: https://ajkdblog.org/2023/03/01/nephmadness-2023-onconephrology-region/#prettyPhoto/10/; No copyright infringement intended.)

Can we re-introduce immune checkpoint inhibitors after resolution of AKI if the tubulointerstitial nephritis?

In the 2020 multicenter retrospective review mentioned above, 31 patients were rechallenged with an ICI after resolution of their initial ICI-AKI, with 7 (23%) recurrences. 6 of those patients responded when re-treated with steroids.

In an international 2021 retrospective review previously introduced, 121 patients were rechallenged, 16% of which had recurrent AKI.

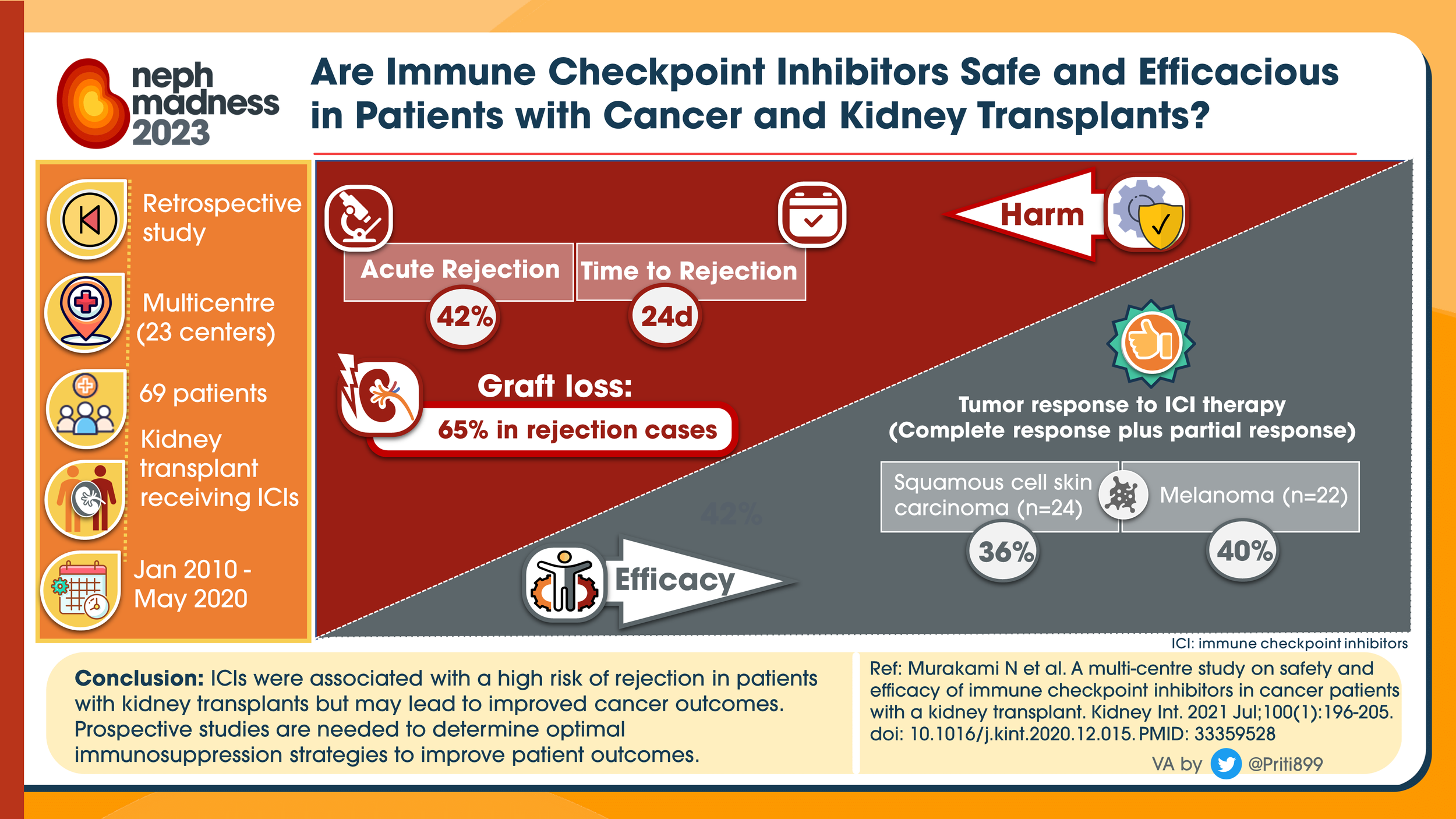

If a patient had a history of ESRD s/p kidney transplant, is it safe to use immune checkpoint inhibitors?

Transplant recipients were excluded in all prospective studies

A 2021 multicenter retrospective cohort study with 69 patients treated with ICI’s between 2010 and 2020 (matched to a non-ICI group) showed an acute rejection rate of 40-45%!

Occurred on average 24 days after initiation of the ICI (range 20-56 days)

Rejection was noted to be half T-cell mediated, and half mixed rejection (antibody and T-cell mediated) or unknown

Of the patients with rejection, 65-85% had resultant allograft failure

However, these studies also noted a significant benefit of ICI therapy on the underlying malignancy, with 35-50% of patients responding with stable to improved disease

In patients with this being the only option, this is risk-benefit ratio

If a patient had a renal transplant and the decision is made that ICI therapy would be beneficial, what measures can we take to mitigate the risk of rejection?

No perfect options:

Can consider low dose pulse steroids, starting 1 week prior to starting ICI and continuing through the therapy

If transplant nephrologist feels it is safe, switching from calcineurin inhibitors to mTOR inhibitor has been shown to have a lower risk of rejection

(Source: https://ajkdblog.org/2023/03/01/nephmadness-2023-onconephrology-region/#prettyPhoto/10/; No copyright infringement intended.)

Match up #2: Chemotherapy-Associated Hypomagnesemia

What are symptoms of hypomagnesemia?

Nonspecific symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting. But when severe can cause muscle tetany, seizures, and arrhythmias

Where is magnesium distributed in the body?

About 99% is stoped as an intracellular cation in bone, muscle and soft tissue

Only 1% is present in th extracellular fluid:

⅓ is plasma protein bound

⅔ is freely filtered

Therefore if blood levels are low, they are really low!

What sort of counseling do we give patients who have hypomagnesemia?

Have a diet high in protein and magnesium rich foods:

Nuts

Pumpkin seeds

Meats

Milk

Peanut butter

All the benefits of magnesium supplements without magnesium tablet side effects

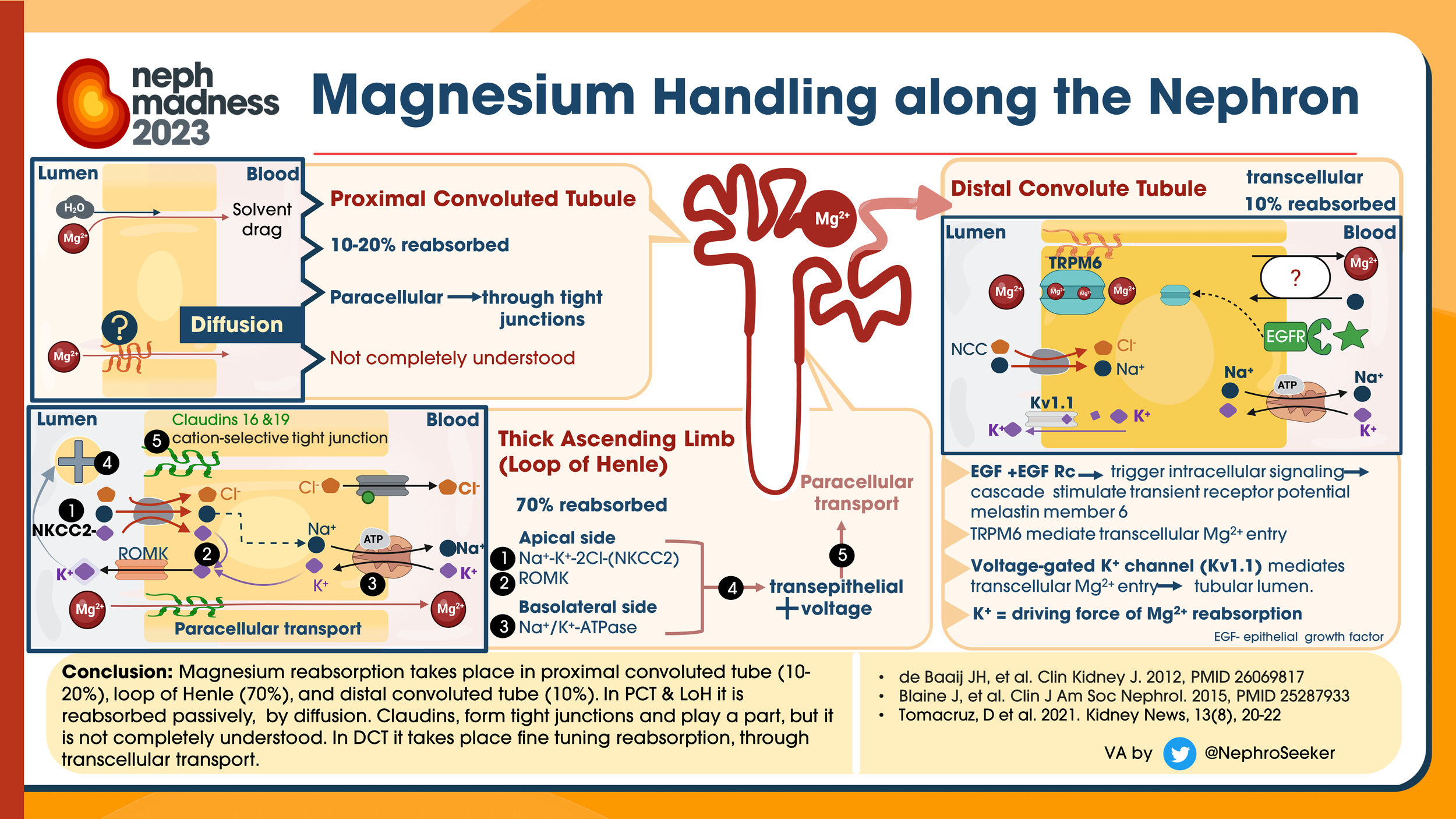

Where is magnesium absorbed when taken orally? How does the kidney help regulate magnesium homeostasis?

The bulk absorption is in the small intestine and is modulated by paracellular tight junction proteins claudin 2, claudin 7, and claudin 12.

There is some in the colon, as well; here it is transcellular via TRPM6 and TRPM7.

Magnesium that is not protein bound is readily filtered across the glomerulus. Approximately 2.4 g magnesium is freely filtered through the kidneys with the majority of this filtrate being reabsorbed.

In the setting of hypomagnesemia, the kidneys are able to reduce this amount of excretion to less than 12 mg per day.

Magnesium is also very readily excreted by the kidneys if needed; it can rid 90-95% of magnesium very quickly in times of magnesium excess

Unlike most electrolytes, the majority of magnesium (⅔) is absorbed in the thick ascending loop of Henle paracellularly

About 15% in distal convoluted tubules transcellularly through TRPM6 channel

(Source: https://ajkdblog.org/2023/03/01/nephmadness-2023-onconephrology-region/#prettyPhoto/10/; No copyright infringement intended.)

What chemotherapies are associated with hypomagnesemia?

Platinum agents have been known to cause hypomagnesemia:

In the earliest phase 1 trials from the 1980s, 10% of patients treated with carboplatin developed hypomagnesemia.

Patients treated with cisplatin were at even higher risk with more than half of the patients developing hypomagnesemia.

What is striking here is that the hypomagnesemia can also persist for 5+ years after therapy is completed suggesting irreversible tubular damage from direct injury to cells in the loop of Henle and distal collecting tubule.

Is there hypomagensemia associated with targeted agents, such as EGFR inhibitors?

A meta-analysis of over 23,000 patients showed that 34% of patients treated with these two agents developed hypomagnesemia, although the severity was quite variable between studies.

A fascinating study of 98 patients with colorectal cancer showed that nearly all (97%) of patients treated with EGFR inhibitors had a negative slope of serum magnesium over time vs a stable slope in controls treated with other chemotherapy.

They even performed 24-hr urinary magnesium and fractional excretion of magnesium (FeMg) in select patients who received EGFR inhibitors, and found mean FeMg levels of 5%, which are inappropriately high in the setting of hypomagnesemia.

IV magnesium load testing in 5 patients was comparable to patients with TRPM6 mutations, implicating renal magnesium wasting as the culprit for the clinical picture.

What was determined was that EGFR-inhibitors downregulate the TRMP6 expression, which impairs magnesium absorption, resulting in excess magnesium wasting

(Source: https://ajkdblog.org/2023/03/01/nephmadness-2023-onconephrology-region/#prettyPhoto/10/; No copyright infringement intended.)

What about adjunctive therapies, such as biphosphates? Do they contribute to hypomagnesemia?

Some adjunctive drugs implicated in hypomagnesemia:

Bisphosphonates

Calcineurin inhibitors

Amphotericin B

PPIs

How do we fix this?

Stop drugs that are unnecessary

Oral magnesium oxide for mild hypomagnesemia

IV magnesium for severe hypomagnesemia

But consider mechanisms discussed here; there is a max capacity of iron that can be taken up

How do dose oral magnesium?

If someone has magnesium wasting, you can’t give enough. Consider 400-800mg by mouth two to three times per day

Oral magnesium oxide is most commonly used but can also consider other formulations if they’re having a lot of GI side effects with magnesium oxide

Consider potassium sparing diuretic that acts to block sodium reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule and collecting duct, which can conserve magnesium

About our guests:

Matthew Abramson: Dr. Abramson is an academic nephrologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in Manhattan, NY. He attended medical school at St. George’s University after which he went to Stony Brook University Hospital for his Internal Medicine Residency. He completed Nephrology Fellowship training at Weill Cornell Medicine, followed by additional subspecialty training in onco-nephrology at Memorial Sloan Cancer Center.

Timothy Yau: Dr. Yau is an Associate Professor of Medicine in the Division of Nephrology at Washington University in St. Louis, MO. He completed his medical school at St. Louis University School of Medicine, after which he went to Rush University Medical Center for his Internal Medicine residency, chief residency, and Nephrology fellowship training.

Scott Stockholm: Dr. Stockholm is a second-year Nephrology Fellow at Washington University in St. Louis, MO. He completed medical school at Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine (Carolinas) and then completed his Internal Medicine residency at Cape Fear Valley Hospital.

References:

Https://ajkdblog.org/2023/03/01/nephmadness-2023-onconephrology-region/#prettyPhoto: NephMadness Onconephrology page created by several amazing contributors

The crew behind the magic:

Show outline: NephMadness Team - Scott Stockholm and Morgan Schoer; TFOC edits by Dan Hausrath

Production and hosts: Vivek Patel, Dan Hausrath

Editing: Resonate Recordings

Shownotes: Ronak Mistry

Graphics, social media management: Ronak Mistry